AMERICAN

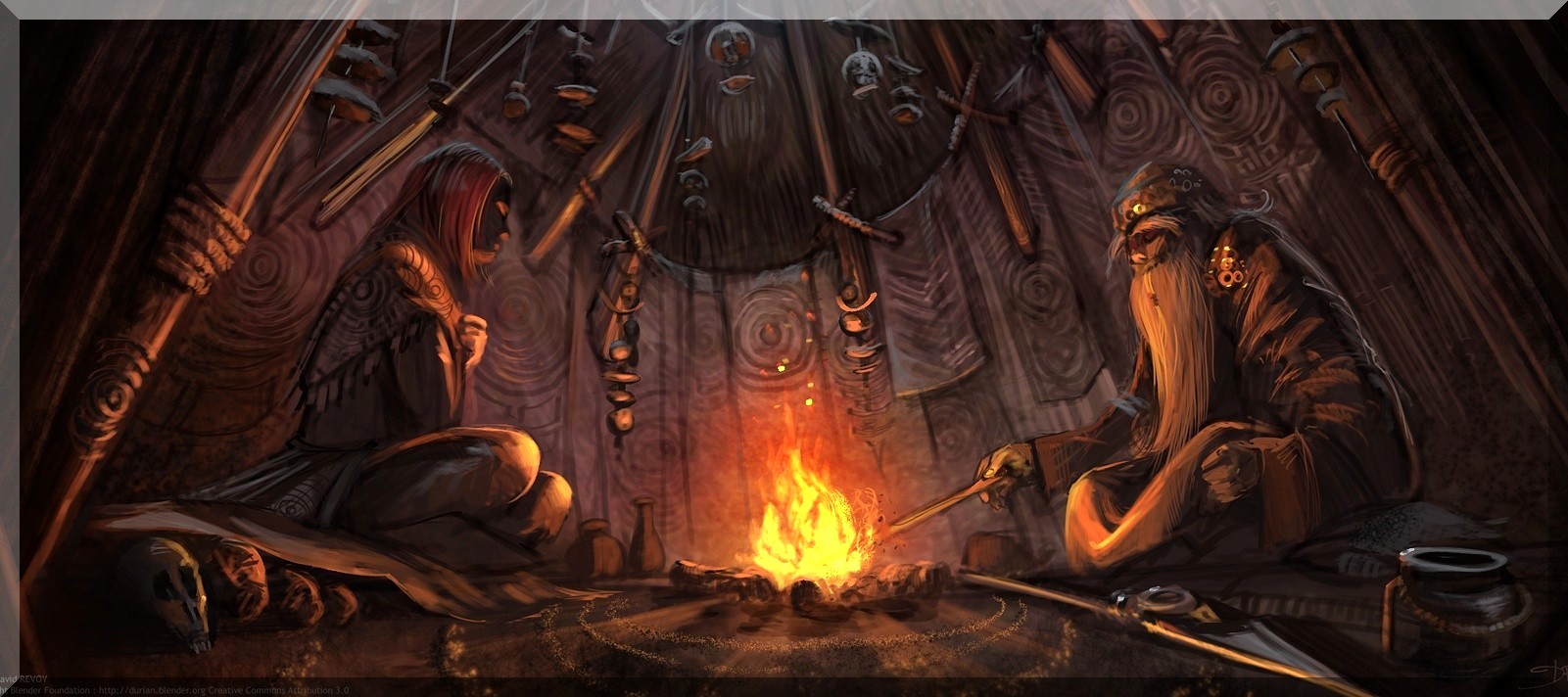

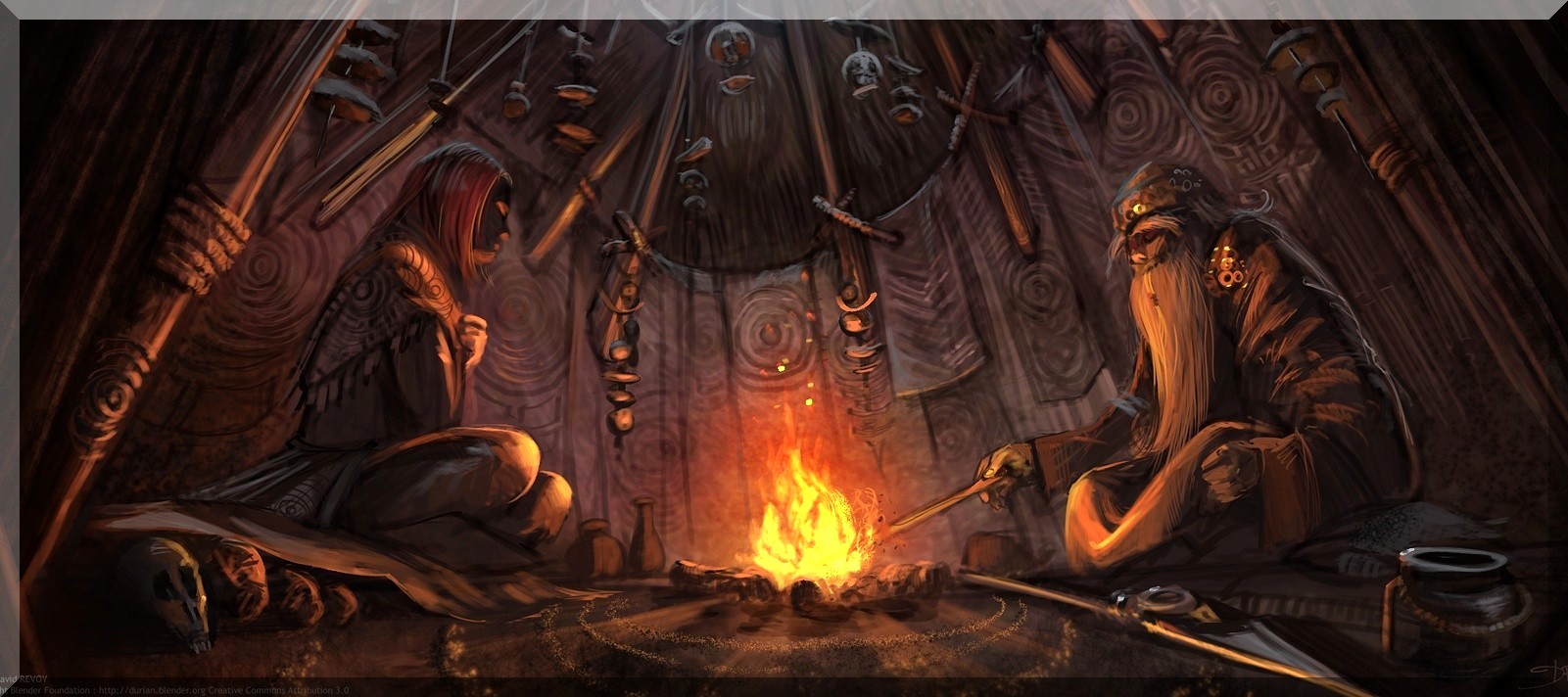

SHAMANISM

AMERICAN

SHAMANISM

AMERICAN

SHAMANISM

AMERICAN

SHAMANISM

Return to American Shamanism Main Page

| Shamans of the

North by Alan Neville copyright 2009 Curiosity without the lack of desire to learn often results in misinformation. This is why so many of the world's cultures are misrepresented and plagued by myth. Many of the world's religions and religious communities are also in a constant fight to clear the names of their religion from the fictitious claims that have tarnished their reputation. The ignorance of people towards the life, culture, customs, history, and religion of the natives of North America is one such example. For centuries, the natives of this land have been religiously oppressed and disrespected in various forms for the better lack of understanding of who they are and what they believe and value. Their way of life is simple and pure and concerns their mental well being as a community through a better connection with their surroundings. The Indians of the subarctic and Canadian north regions have for many centuries, through oppression and religious and cultural intolerance, practiced and held firmly on to Pagan and Shamanic beliefs to form a rich bond with nature, their inner souls, and their Gods. The Natives of North America have seen their religion, language, customs, and culture oppressed by the white man who arrived on their land centuries ago. These people who enjoyed and cherished the land that gave them so much have always been treated as second class citizens, and not until recently did the Canadian Government acknowledge the “immense toll of suffering still being felt in the native population resulting from cultural loss, separation from families, and victimization through physical and sexual abuse” ( Niezen, 2000, p. 86). The mis-portrayal of their culture is an ongoing problem. Many, still today, see natives, their culture and religion, as a threat to their civilized society. Since early colonization by Europeans they have seen the Natives “...as living in a state of savagery that was a danger to their health, prosperity, and salvation.” ( Niezen, 2000, p. 86). To the early settlers of North America the native traditions held no value and was seen as primitive savagery, and “indeed, getting drunk and killing Indians was sport to most settlers...who maintained that to kill an Indian was the same as killing a bear or a buffalo.” (Mann, 2005, p. 5) The Natives had developed rich traditions and had no interest in European religions, especially Christianity who they were beginning to see as “a main prop of genocide” (Mann, 2005, p. 150). They were beginning to see vast differences between the religion of worshiping and thanking nature and multiple Gods and Christian values and beliefs. The Christians slaughtered the Indians opportunistically both in the North and South. An example came in the fall of 1864: Colonel Chivington, who was also a Methodist minister carried out a bloody massacre on the Cheyenne people. His men killed hundreds of peace loving Natives because he believed their extinction to be beneficial to his country (Monnett, 1999, p. 8). It may have been different if men like these took the time to understand the Native way of life and religion. They were taught that the natives practiced simple and meaningless religions such as Paganism and that it was their uncivilized approach that was to blame (Beecher, 1962, p. 1). They would either have to assimilate or be rendered extinct because Paganism and Shamansim was considered evil. As mentioned, even today the religions and rituals practiced by the Natives is not clearly understood. Many North American natives are essentially pagans. They are polytheistic, finding it more compatible with their beliefs and their ancestral way of life. Polytheism is the belief that multiple Gods have ruled the earth since the beginning. Some cultures, perhaps even the early Athabaskans, gave these Gods names and identities. They worshiped and prayed to them for their good fortunes and asked for help in times of desperation and drought. The early natives of North America, like the Pagans of ancient times, have maintained the strong belief in polytheism. In fact they each in some form believe that “no one Deity can express the totality of the Divine” (Peters, 1990, p. 77). They not only believe that there are multiple Gods, each perhaps ruling one aspect of the earth, they also believe in pantheism, or the belief that the Gods are everywhere in nature and within their bodies. Different tribes have valued different aspects of such a way of organized belief; however, most do believe in somewhat similar things. For instance, dancing and praying to the Sun God is common. Unique rituals that they practice to bring in the good spirits and fight off the bad ones is also pretty common among the different tribes (Stutley, 2002, p. 2). Pagans and Shamans share many similarities and have been popular examples among the natives of the subarctic region throughout history. It can be argued that the Shamanic belief system was developed from their way of life. It may have been an essential belief system for the survival of their people. Regardless of such theories, it is obvious that the Shamanic Inuit have a deep admiration and respect for their environment. Many natives believe that at the beginning humans and animals were the same and could morph back and forth between either form. They believe that throughout time they made a full separation in to two different types of entities. This, then, essentially supports their point that humans and their animal friends need to have a profound admiration of each other and protect each other's way of life. According to Venables and Vecsey: This curious, unitary view of human and animal genesis prevails throughout the Canadian Subarctic...both men [Athapaskans in general] and animals . . . possessed essentially the same characteristics' when the world was new...'In the beginning of the world, before humans were formed, all animals existed grouped under 'tribes' of their kinds who could talk like men, and were even covered with the same protection.'...acknowledging that after the passage of untold generations the two were still, after all, spiritually akin. It is easier to see that the Athapaskan natives took their surroundings very seriously and respected their animal brothers. This sheds some light in to the natural progression to the Shamanic belief systems that they developed over time. Furthermore, Shamanism is a religion that has had many variations. It has been around for centuries and has been encountered all over the world. In recent centuries, up to the present day however, it has been misunderstood, especially by conservative Christians who see it as the “devil dance”, devil worship, and even heresy (Macdonald, 2002, p. 52). Shamanism is a beautiful religion and one that is relatively simple and peacefully practiced by the natives of the north. According to Stutley, Shamanism is more complex than other centrally-organized religions and is hard to study because of its many various forms. However, she goes on to mention that all Shamanism have three common aspects: (1) belief in the existence of a world of spirits, mostly in animal form that are capable of acting on human beings. The shaman is required to control or cooperate with these good and bad spirits for the benefit of his community. (2) The inducing of trance by ecstatic singing, dancing and drumming, when the shaman's spirit leaves his or her body and enters the supernatural world. (3) The shaman treats some diseases, usually those of a psychosomatic nature, as well as helping the clan members to overcome their various difficulties and problems. Firstly, the spirit world, as mentioned, is essential to the Shamans of the Subarctic region. The Shaman believes strongly that every object on earth, living or not, has some form of spirit connection. However, the important thing for the Shaman is to be connected with the right spirits and fend of the evil ones. For example, “Hunters seek animal guardians who can bestow success in the hunt; warriors seek specialized powers to enhance their war shields and weapons” (Andrews, 1998, p. 196). Furthermore, some Shamans are believed to have a profound connection with the spirit world. Some even go as far as believing that Shamans, as healers or medicine-men of their communities, not only have the ability to call upon the spirit world but to become powerful animal spirits themselves (Jakobsen, 1999, p. 1). In addition to this, many Shamans believe that the human to spirit connection manifests itself deeply in dreams. They believe that many of the answers to life's problems can be aided by the spirits around them through the power of dreams. It has been, therefore, a common belief that sickness and disease are due to an imbalance of spirits, or the work of bad spirits haunting the person (Mowszowski, 2001, p. 14). Furthermore, the Shaman is seen by some as a necessity in linking the spirit world with our physical world. At some point the power of the Shaman, then, became that of “mediator between spirits and human beings (Lewis, 2003, p. 41). The Shaman would use his power to bring the people of the tribes closer and in harmony with the spirit world. To others in various tribes, Shamanism is a way of reducing the stress and fear of the unknown. Often, in times of stress, hunger, and chaos the Shamanic belief system is relied upon to reduce tension, stress. Essentially, as Jobsen puts it: “The shaman's role is to reduce the fear of these forces and establish a balance in society as a whole...often the shaman is the only one who can travel to the spirits because he knows the way” (Jacobsen, 1999, p. 2). At times of total concentration and connectedness some Shamans believe that they can enter the spirit world and “go into battle with the malevolent spirits of the dead, thought to be the cause of illness and death...” (Furst, 1996, p. 20) They also believed that things from one world had effects in the other. For example, Mowszowski also notes that some Shamans believed that rain was a manifestation of bloodshed of animal spirits in the spirit world (Mowszowski, 2001, p.14). Naturally, we must admit that the Shamanic aspect of trance and meditation is profoundly interesting. Many Natives, along with the people of other regions, have throughout time, held on to their belief that the soul has the ability to detach from their physical body. They believed that the only thing that they really had in their possession was the physical flesh. After a deep trance, they believed that they gained the ability to send of their soul to the spirit world. In return for their soul flying off, a spirit from nature would enter their body and take over. Still other practitioners believed that a “shaman's body can be concurrently occupied by several ghosts or spirits as well as by his own spirit or soul” (Ross, 1997, p. 211). The Native shamans grasped on to this type of notion and made it an important part of their life and culture. Every part of their daily life began to have a connection to the spirit world as it not only gave them a sense of meaning and purpose but a very magical and romantic explanation of their surroundings. However, it must also be noted that the establishment of the trance state is not only a means to build a connection to the spirit world or communicate with the Gods. The achievement of a trance state was always important for the enjoyment of a heightened awareness, or ecstasy (Lewis, 2003, p. 43). It helped the Shaman achieve total peace and tranquility and be a part of nature. This then helps us understand the Shamanic Indian's passion for “natural” highs. They have through time developed a complex understanding of nature's trance-inducing drugs, especially the hallucinogens like Peyote and wild, or magic, mushrooms. They were an important part of the Native Indian's religious rituals and ceremonies and helped them achieve a heightened awareness. As Schaefer describes in her book, People of the Peyote, “...the divine peyote cactus...stands at the center of the shaman's universe...It functions as ally, protector, and facilitator of the ecstatic trance in which the specialists in the sacred interact directly with the gods and seek their advice” (Plotkin, 1990, p. 9). The natives found that the trance state induced a dream-like event which helped them find answers to their problems. They believed that the solutions to many of their problems were hidden deep in their dreams. Therefore, the use of these chemicals was vital to their overall health and survival. The Shaman way of life was indisputably essential for the over all health of their community. A huge part of their belief system consists of the fact that the Shaman religion or way of life gives them the power to heal. Through their use of connectedness with nature and the communication with the spirit world and Gods, as well as their rich understanding of the vast body of organisms in their surrounding environment, they became effective healers. Shaman medicine men have been popularized in modern times and have been turned in to almost mythical figures. Many see them as witch doctors whose healing powers parallel that of the priest who performs exorcisms. However, many of this holds no merit. While it is true that Shamans have historically performed exorcisms, they have also played a major role in keeping the physical and mental health of their communities in good shape. Specifically, many Shamans used their role and prestige in their community to help mentally-ill Indians heal and integrate them back in to their society. Their understanding of medicine and mental processes was integral to this. As Ross describes: “...the shaman and the mythology shared by him and the patient alter physiological processes through the control of mental processes, dissolving the boundary between self and other and offering reintegration to the patient (Vecsey, 1980, p. 38). It is also not uncommon for a Shaman, or medicine man, to know well over a hundred plant species capable of healing numerous diseases and infections. This knowledge had been passed down to the natives, generation to generation, and used effectively to cure. At some point traditions became suppressed by the ideas brought in by the settlers and modern medicine began to replace the Shamanic way of traditional healing. We can, therefore, see that the Native religion is vastly different than what the media and governments have portrayed over time. The natives of many regions, and specifically those of the subarctic for our purposes, have found Shamanism as vital to their survival and over health and well being. Shamanism and similar faiths provide a way for the subarctic natives to hold a close bond with their environment. Furthermore, it has given the natives the foundation to build technologies and develop methods and tools to better understand life. The Shamans have had a simple life style that preaches a deep connection with the Spirit world and the use of the spirits, Gods, and their environment to understand their purpose, their brothers, and to find healing potential in their way of life and religious practice. Bibliography Andrews, Terri J. (1998). Living by the Dream: Native American Interpretation of Night's Visions. World and I 13 (11), 196. Beecher, Bronson E. (1962). Reminiscences of a Ranchman. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Bernstein, Jay H. (1997). Spirits Captured in Stone: Shamanism and Traditional Medicine among the Taman of Borneo. Boulder: Rienner. Crowley, V. (2000). Paganism. London: HarperCollinsPublishers. Furst, Peter T. (1996). People of the Peyote. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. Jakobsen, Merete D. (1999). Traditional and Contemporary Approaches to the Mastery of Spirits and Healing. New York: Berghahn Books. Lewis, L. (2003). Ecstatic Religion: A Study of Shamanism and Spirit Possession. New York: Routledge. Macdonald, G. (2002). Shaman or Sherlock? The Native American Detective. Westport: Greenwood Press. Mann, Barbara A. (2005). George Washington's War on Native America. Westport: Praeger. Monnett, John H. (1999). Massacre at Cheyenne Hole: Lieutenant Austin Henely and the Sappa Creek Controversy. Niwot: University Press of Colorado. Mowszowski, R. (2001). Rocks of Ages. Geographical 73 (8), 14. Niezen, R. (2000). Spirit Wars: Native North American Religions in the Age of Nation Building. Berkeley: University of California Press. Peters, L. (1990). Mystical Experience in Tamang Shamanism. Re-vision 13 (2), 77. Plotkin, Mark J. (1990). The Healing Forest: The Search for New Jungle Medicines. The Futurist 24 (1), 9. Romanucci-Ross, L. (1997). The Anthropology of Medicine: From Culture to Method. Westport: Bergin & Garvey. Stutley, M. (2002). Shamanism: A Concise Introduction. London: Routledge. Vecsey, C., Venables, Robert W. (1980). American Indian Environments: Ecological Issues in Native American History. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. Vernon, Irene S. (1999). The Claiming of Christ: Native American Postcolonial Discourses. MELUS 24 (2), 75. |